Slowing down age-related declines for Masters athletes

With a detailed look at weightlifting

I’m 55 years old and compete in Masters Weightlifting. I also have several elder relatives in their 80s who have seen a rapid decline in their health. I’m interested in what we can do to improve their quality of life, and also what I can do to improve my performance.

It turns out the solution to both problems is similar but at different intensities. I have previously discussed resistance training for health; this article focuses on performance.

(N.B. This isn’t a Jeff Bezos-like post about being in denial about ageing, so skip it if you want to freeze yourself cryogenically or harvest cells from infants.)

Old or inactive?

It’s hard to separate what is ‘natural’ ageing and what is a lack of activity. Still, if you go to a family barbecue one weekend and then go to a Masters weightlifting competition the next, you might become an immediate advocate for exercise (unless your family are all masters lifters).

Both groups of people might be grunting and wheezing, but the former do it when they get up from a low chair and stagger across the lawn to pick up their burger, while the latter do it when lifting more than their body weight above their head.

At some point, we move from occasionally falling over to ‘having a fall.’ I dislike the latter phrase immensely: it’s changing the act of falling to a passive, receptive state. The two main reasons for falling are:

Weakness

Poor balance

The causes for weakness and poor balance are many (including the number of medications you are on: 5 types of medications increases your risk significantly (1)), but inactivity is a factor. Prolonged sitting at work and at leisure, avoiding manual tasks at home, such as gardening, housework and walking the dog, and stopping participation in ‘team’ sports all lead to a decline in fitness.

Unfortunately, the spiral of decline can be triggered by a disease and/or accident. A forced rest means that fitness is lost. Once easy-to-manage tasks become difficult, and so they may be avoided. This results in less movement, less fitness, and so on.

Once recovered, the important thing is to resume training as soon as possible.

Tip 1: If falling is prevalent in the aged, then working on strength and balance to reduce the risk seems like a good idea.

What is causing the performance decline?

But if you are committed to remaining active and have avoided serious illness or injury, why is your performance declining? What is it about ageing that is slowing you down?

A review of anaerobic performance in Masters Athletes found that there was a linear decline in performance from 35-70 years old, followed by a steeper decline from then on (2).

Women experience a steeper decline than men after the age of 40 due to ‘hormonal changes’. While this two-word phrase is succinct in a research article, the menopause is massively impactful for many women. Unfortunately, it is under-researched in female athletes at present. More is needed.

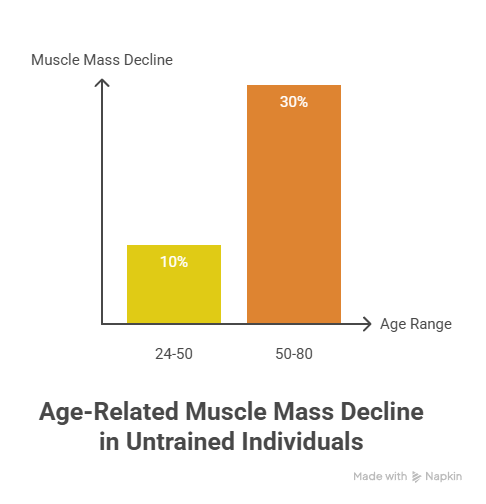

One of the major reasons for the decline in both sexes was the loss of muscle mass. A decline in muscle mass is ‘normal’ in untrained individuals. Although your weight may stay the same between 24 and 50, your body composition is likely to change: for the worse!

Once you get past 50, things (and body parts) go downhill rapidly.

If you are competing in any sport (not just weightlifting), the loss of muscle mass will impact your performance. The type II muscle fibres appear to atrophy the most, which results in a decrease in the speed of muscle contraction, slower enzyme activity and an increase in lactate production.

If you are playing a sport without additional training, then you will struggle to keep up with the younger ones running rings around you (I found this out the hard way and gave up MMA at the age of 41: it wasn’t much fun getting my head pummelled into the ground by a 19-year-old who was 20 kg heavier than me).

The good news: training works!

Hooray!

A review of Masters Athletes found that:

“Despite advancing age…chronic exercise training preserves physical function, muscular strength and body fat levels similar to that of young, healthy individuals in an exercise mode-specific manner.” (3).

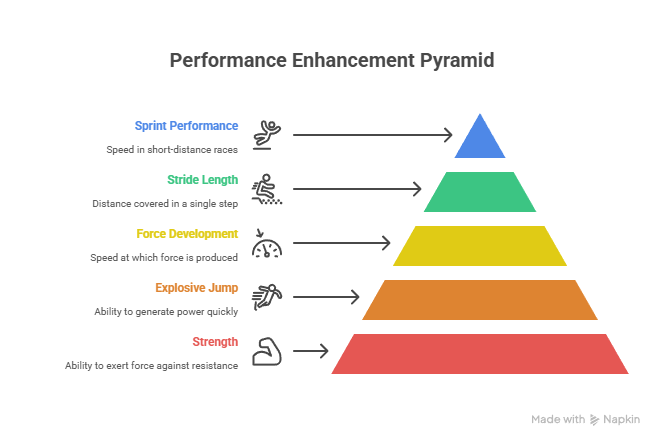

The declines in these performance markers: strength, explosive jump performance, rate of force development, stride length, and 10-meter and 60-meter sprints, can be slowed with the correct training.

The best way to do this? Strength training, working towards heavier loads, was key to maintaining muscle mass. This included machine weights and free-weight exercises such as squats, pulls, deadlifts, and presses.

Short sprints (not jogs) and jumping training helped maintain power and the rate of force development. Jumps can include: broad jumps, hops, bounding and combinations of movements.

Weightlifting exercises, and their derivatives, require both speed and strength and improve the rate of force development. This includes: snatch, cleans and jerks. These require technical proficiency and a level of mobility not required for machine weights. If you wish to start these, find a good coach.

Two of the major risk factors for injuries in master weightlifting athletes were:

writing their own program (especially men).

Either prior or current experience with CrossFit. (4).

Tip 2: Combining high-intensity sprints with strength and power training helps you maintain muscle mass and significantly slows the age-related decline in performance.

Remember, we are not in denial about ageing, but we want to do our best to stay healthy for as long as possible. Much of what is seen as ‘age’ is simply a lack of use.

Activities such as weightlifting and short sprints can help increase your health span.

Sample programme for a Masters’ Weightlifter (in their 50s).

I work on a 5-week strength build-up followed by a 3-week conversion and then a 2-week taper/sharpening block before each competition. As I did 6 competitions last year and have done 3 already this year, it doesn’t leave much spare time!

If I do get time, then I do an easy unload week and then a ‘ramp-up’ week before I start the next block. I use these times to work on circuits, agility, some speed and hypertrophy. Basically, everything without a barbell.

I only do 3 weightlifting sessions a week. I’ve tried four, but I can’t manage it: I’m tired after the first two sessions. I don’t know many lifters in their 50s who are training four times a week. This also fits into my life, rather than my life fitting around weightlifting (despite what my wife says…).

Strength Block.

Session 1: Warm -Up (Movement, plus structural integrity exercise). Then barbell exercises.

Snatch: Mid-thigh x3, Hang x3, Floor x3 x5. (All exercises are reps/sets).

Clean Pulls: 5x3

Jerk from Rack: 3x5

Front squats: 5x5 (weeks 1-3) 3x5 (weeks 4-5).

Session 2: Warm -Up (Movement, plus structural integrity exercise).

(1 power snatch +3 snatch balance + 5 sotts press), 3 sets, increasing the weight.

Snatch: mid-thigh x3x4.

Power cleans: 3x5

Push Press: 5x5.

Back squats: 5x5 (weeks 1-3) 3x5 (weeks 4-5).

120kg back squats (1.5x bodyweight).

Session 3 (lighter): Warm-up (movement, plus structural integrity exercise).

Snatch: Mid-thigh x3, Hang x3, Blocks x3x2, 2x3.

Snatch Pulls: 5x5.

Push Press: 5x4.

I’m tired and ready to move on to the conversion phase at the end of this block! The next five weeks look like…

References

Being Mortal: Atul Gawande (a good book about ageing and caring for the elderly).

Anaerobic Performance in Masters Athletes. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act (2009) 6:39–53.

Muscle Performance and Morphology in Masters Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Ageing Research Reviews 45 (2018) 62–82.

Health challenges and acute sports injuries restrict weightlifting training of

older athletes. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2022;8 p1-8.